NZIFF 2017: WARU Is The Best New Zealand Drama In Years

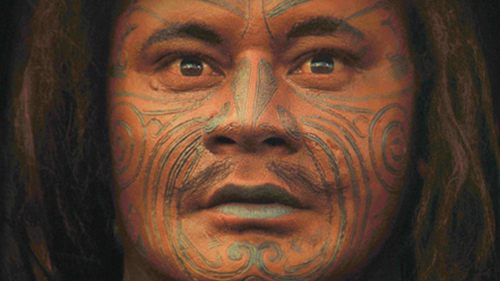

There have been many brilliant films directed by New Zealand Māori throughout the years, from Utu to Once Were Warriors up to What We Do In the Shadows. Indeed, the work done by Māori filmmaking creatives has arguably done as much as any New Zealand art to define New Zealand culture on the world stage. Consider the success of Taika Waititi, whose films Boy and Hunt for the Wilderpeople both garnered international acclaim and concern themselves with homages to growing up Māori, or the rapturous reception to Whale Rider in the early noughties. There is always work to be done, but Māori filmmakers are consistently proving themselves as vital creative voices in the modern age, not just in New Zealand but internationally as well (further proof – the upcoming Thor: Ragnarok is directed by Taika Waititi). There have been several wāhine Māori artists who were pioneers in the field – Merata Mita (whose Mauriis the only narrative feature with a solo director credit for a wahine Māori, all the way back in 1988) and Ramai Hayward, among others – but the chances to see this important aspect of indigenous representation up on screen have been sadly few and far between.

That changed last night with Waru, a remarkable, moving film that is certainly assured as the finest film coming out of New Zealand this year, and the best New Zealand drama since at least The Dark Horse, if not Robert Sarkies’ true-crime masterpiece Out of the Blue. The result of a fascinating experiment to bring together a number of wāhine Māori both in front of and behind the camera, Waru tells the story of myriad lives colliding when a young boy (the Waru of the title, which also translates to the number eight) is killed at the hands of domestic abuse in rural New Zealand. The catch: the film is divided into eight ten-minute long sequences, each a single take and each directed by a different wahine Māori director, each focussing on a different wahine Māori character. As a technical experiment alone, its ambition is unmatched in New Zealand filmmaking history, especially considering the budget restrictions the film was saddled with (as most New Zealand dramas are) – however, the fact that the film coheres and delivers so consistently and so powerfully elevates it beyond a mere experiment or gimmick in ways both laudable and immensely socially relevant.

The film is brief, spanning just above 80 minutes, but by the end of the eight films I felt like I’d run a marathon. So detailed and lived in are the characters and locations that I found myself only able to reflect on the authenticity that voices within the culture bring to cultural stories –Waru is many things, but it is foremost a reflection on the importance of not only telling the stories of different viewpoints and cultures, but of the necessity that the telling of these stories reflect the actual experiences of those who live them. That the film transcends the experimental structure of its storytelling to elevate to something cohesive and whole reflects the level of synchronization the women at the helm – Briar Grace-Smith, Casey Kaa, Ainsley Gardiner, Katie Wolfe, Chelsea Cohen, Renae Maihi, Paula Jones and Awanui Simich-Pene – had with each other. Every story is subtly different, containing different flourishes of directorial ambition, but all are laser-focused on capturing the very real social issues that plague this indigenous community and particularly the role of wāhine Māori in solving those issues. So much of modern New Zealand film seems to have moved to a place separate of capturing and speaking to urgent New Zealand issues – reflecting a general desire to push out the idea of a country as close to ‘paradise’ as possible, one devoid of problems, so it is commendable that Waru never succumbs to sentiment or glosses over the issues of abuse both in Māori communities and in New Zealand society as a whole (a staggering statistic – a child is killed because of domestic abuse in New Zealand every five weeks). This is issue-based filmmaking as high-wire ambitious, righteously angry and spirited as any New Zealand drama I’ve come across – one that represents a huge group of wāhine Māori throwing their all at the screen in poetic and surprising ways.

The one-shot framework of the film is certainly virtuoso, and the work of cinematographer Drew Sturge and his camera crew is nothing short of remarkable, considering the film is not anything close to the blockbuster budgets this kind of camerawork generally requires. The one-shot take in cinema has a long and storied history, too often simply a literalization of the director’s desire to show off their technical mastery but lacking any real motivation or narrative reason for being – camerawork that draws attention to itself as in Inarritu’s Birdman and The Revenant. The best one-shot takes are immersive, capturing an overwhelming sense of disorientation and ‘in-the-moment’ world-building that reflects a place of tension or action or even elation on the part of the characters – think Children of Men, or Boogie Nights. Waru is emphatically of the latter camp, every new take clinging to its subject like a child gripping a parent’s arm, pausing to capture occasional grace notes in every story – as in the film’s best sequence, when two proud kuia (older wāhine Māori of significant substance in their community) debate the final burial site of Waru. The camera spins dizzyingly around the two as they battle over the body of a child, occasionally weaving off to capture the faces of the others gathered around or to examine the faces of long departed ancestors whose pictures line the walls of their Marae (or meeting place).

As with any work of large-scale creative collaboration such as this, certain elements work better than others. Contrasting with the brilliance of the kuia scene (which acts as a kind of Malickian anchor in the centre of the film), other segments jibe slightly with the tone and aesthetic of the larger story – most notably a segment that reflects the New Zealand media’s reaction to the story that takes on worthy targets of misinformation and uninformed opinion-making in the white New Zealand populace, but digs into satire in a broad manner that seems to have walked in from another film. However, a mark of the film’s strength is that its imperfections ring as truly as its many successes – every segment is deeply felt, impassioned, community-based filmmaking that reflects the importance of Kotahitanga – or unity – in Māori society as effectively as it does in the filmmaking process in general.

Several of the best segments of the film (namely its seventh and eighth) end on staggeringly powerful moments of tension, capturing a moment seconds before conflict, that acts as one of the few justified and motivated moments of direct address fourth-wall breaking that I’ve seen. This is assured through the passion both in front of and behind the camera and, in the process, reveals a number of rising stars in the New Zealand film scene (in particular, some startlingly powerful work from Acacia Hapi as a young woman fighting back against institutionalized abuse, and Tanea Heke as a wonderfully brittle Auntie trying to manage a hectic Marae kitchen). As a call to action, New Zealand has not seen a work as powerfully filmed, conceived and performed as this in many years. This is urgent, ambitious filmmaking that proudly exclaims the importance, vitality and spirit of wāhine Māori for a wide audience, and is the best New Zealand film of the year. Don’t miss this one.