UNSANE Review: To Avoid Fainting Just Keep Repeating “It’s Only A Movie…”

During the early '70s, there was a time when legitimate artistic maniacs were being given access to cameras and allowed to shoot whatever their twisted hearts desired. Wes Craven's The Last House on the Left ('72) is probably the best example of this – a rough, undisciplined, handheld descent into torture and madness that genuinely felt like it was being transmitted from the diseased mind of an asylum inmate. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre ('74) is another, a primal howl of rage against Vietnam and the innocence that conflict stole from America, transmuted into a nightmarish travelogue through the bowels of a rural Hellscape. These movies took a medium and pushed it forward in a way that felt nasty and unsafe – real horror delivered by those just learning what the hell this device on their shoulder can do when freed from the confines of filmic "rules."

Unsane is Steven Soderbergh's Last House On the Left. It's his Texas Chain Saw. Where the notedly experimental director already aped Brian De Palma with his severely underrated Side Effects in 2013 – a playful reworking of the "erotic thriller" that also acted as a sly commentary on Big Pharma – this is the auteur making his equivalent of those early DIY horror classics that scared the ever-living shit out of anyone who dared lay eyes on them. Only instead of a mobile Bolex, Soderbergh is again stretching the limits of digital cinema by shooting Unsane on an iPhone, resulting in a rough, hardened vision of one woman's (Claire Foy) battle to convince everyone she's still stable. However, wrapped in this tale of involuntary commitment is an (un)healthy dose of commentary regarding consent, gaslighting, the insurance industry, and how we view women who've apparently "lost it" in the face of unending harassment. In short, this is Wes Craven for the #metoo generation.

While its title is a deliberate nod to Dario Argento, there's a lack of formal control present in Unsane that's live-wire and electric. Soderbergh is using the tiny lens from his pocket to free himself from traditional set ups, often placing us in the face of Foy's Sawyer Valentini, a corporate ladder-climber who's still trying to shake off the fear she's been living with since a stalker invaded her life not too long ago. Despite Sawyer's obvious power and intellect, the men who surround her still only see a pretty young thing in a pantsuit. After rejecting her boss' (Marc Kudisch) advances, an attempt to get laid on Tinder – or, at least, this twisted universe's version of Tinder – ends in the woman having a slight breakdown. It seems Sawyer's going to need some professional help ridding herself of these demons, so she seeks out a counselor (Myra Lucretia Taylor) at a local health facility, who’s obviously upset when Ms. Valentini talks about the very specific ways she's considered suicide. Following a few signatures on some paperwork, the institution can talk about "next steps" toward her achieving recovery.

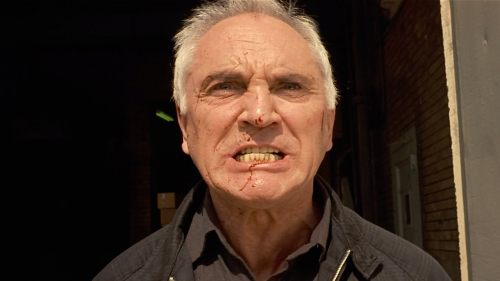

Unfortunately, those few strokes of a pen sign away Sawyer's freedom, as she finds herself escorted to an exam room, before being fitted for a hospital gown and told she's not allowed to leave over the next twenty-four-hour “observational period.” Despite begging and pleading with orderlies, the administration, and even the other inmates – including the corn-rowed, sneering Violet (Juno Temple) – that she's not crazy, nobody wants to listen. They've heard these cries before and know they're all bullshit. So, desperation leads to violence, as Sawyer lashes out – initially slapping male nurse Dennis (Zach Cherry) – before engaging in increasingly explosive episodes. Now, “twenty-four hours” has been extended to “seven days”, and even her own mother (Amy Irving) can't talk the powers that be out of this commitment. Sawyer’s stuck in this snake pit for the duration, all while side-eyeing the attendant who hands out the patients' daily medication (Joshua Leonard). She knows he's not who he says he is. That's her stalker, David Strine. But how the hell did he get in here? Or is she truly losing it inside this nuthouse?

Michael Mann has always maintained that he switched from film to digital because he adored the immediacy pixels brought to every movie he made, and you have to wonder if Soderbergh is attempting to take this theory one step further with his iPhone cinematography (which the filmmaker again shoots himself under his usual pseudonym, Peter Andrews). There's a leering, skewed POV to every composition, as the phone's vertical aspect ratio isn't cropped or re-formatted to fit your screen. Instead, it leaves a little too much headspace in close-ups, and the depth of field seems limitless, as we notice every moving detail of the rooms we're in while trying to focus on the dilemmas at hand. It's a truly thrilling new visual schematic, adding this untested sense of "you are here now, deal with it" paranoia to each moment, the intensity building even when seemingly nothing is happening. Due to this overwhelming dread, we're double-guessing every movement Sawyer makes just as much as she is, the seemingly endless corridors of this hospital becoming downright Kubrickian thanks to the unmanageable height of Soderbergh's frame.

Bringing a sense of social awareness is the character of Nate Hoffman (Jay Pharoah) – a mild-mannered addict trying to kick his opioid addiction who, like Claire, doesn't seem to belong in this place. Hoffman warns Sawyer about how her predicament is probably part of an insurance scheme. She mentioned "suicide" – a trigger word that allows the institution to immediately sign their patients up for commitment due to the individual being "a danger to themselves and others" – and now they'll milk Blue Cross Blue Shield dry until tossing the noted threat out onto the street, their status as a walking ATM no longer applicable. It's just a theory he has (or is it?), but now even the staff who tell Ms. Valentini that they're merely operating "in her best interest" can’t be trusted. Are they really? Or is this incarceration simply a capitalist scheme on the care provider's part, with Pharoah playing this story’s iteration of Johnny Barrett, out to expose abuses of power with his own hidden cell phone and calm, collected demeanor.

As good as Pharoah is – and he truly becomes the conscience of this demented digital reverie – Foy is the real story in Unsane, using her often impossibly gigantic eyes to convey fear, doubt, sadness, rage and a myriad of other emotions as Sawyer struggles to keep it together over this week-long journey into mental oblivion. By the time she's been poked and prodded in almost every fashion imaginable – bouncing off the padded walls of a basement isolation cell while keeping watch on the door to make sure David doesn't creep in – Foy has transformed into an avatar for every abused, neglected, and unheard woman whose concern led them to be labeled "crazy”. For all the cheeky jabs at insurance companies, there's also some sociopolitical allegory tossed into Unsane for good measure. A whole movie where a woman has been committed, against her will, because she didn't read the fine print, only to be harassed by a maniacal man in power who wants to do nothing more than possess and control her body (and damn her if she refuses)? Sounds unsettlingly familiar.

There will undoubtedly be many who write off Unsane as Soderbergh just fucking around, and to a certain extent that's true. This is the same artist who jumped into the digital cinema arena very early and delivered the wholly forgettable Full Frontal ('02). But in the grand scheme of horror, Unsane possesses the same elemental power of those game-changing exploitation shockers, capturing the imagination of generations because they upended the way we look at genre cinema as a whole, often without us recognizing it until years later. Soderbergh has been a consummate mad scientist throughout his career, and Johnathan Berstein and James Greer's script seems like the perfect blueprint from which he can construct this digital haunted house of the mind. Upon reaching the picture's final harrowing freeze frame, it's clear that Soderbergh’s out to wound and scar the audience with unrepentant nastiness that reflects clearly defined real world fears. So, just in case you get too scared while watching Unsane, keep repeating to yourself, "it's only a movie...only a movie...only a movie...only a movie..."