BUSTER SCRUGGS’ “The Mortal Remains” And The Coen Brothers At Their Most Vulnerable

Spoilers for The Ballad of Buster Scruggs to follow.

In my favorite Coen brothers film, The Big Lebowski, Bunny tells The Dude her boyfriend, Uli, is a nihilist. “He believes in nothing” Bunny says. “That must be exhausting,” The Dude replies.

I’ve talked with a lot of people who were exhausted after watching the Coen’s latest movie, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Even by the standards of their bleak filmography, Scruggs alternates between emotionally ruthless, dark, cynical amusement, and bleak nihilism. Want to see a segment in which a man with no arms or legs drowns in a river? This movie’s got you. Want to watch a lonely man and woman sweetly fall in love, only for the woman to commit suicide due to a tragic misunderstanding? That’s there too. Want to see a more bubbly version of Anton Chigurh from No Country for Old Men run rampant through a Western town? That’s the first story!

Several people I’ve discussed the movie with - even those who liked it - felt so beaten down by the movie that they barely engaged with the final story, "The Mortal Remains." Maybe that’s why most seemed to have missed that it’s one of the most personal the Coens have made, a revealing explanation (or as close to an explanation as Joel and Ethan will ever get) for why the Coen brothers make movies at all, what they’re hoping to accomplish, and how there’s actually a very human, empathetic heart beating underneath their fatalism.

"The Mortal Remains" takes place almost entirely on a stagecoach manned by a mysterious rider who seems an awful lot like Death himself, hurtling five people toward the great beyond. The passengers are a trapper, a religious woman, and a Frenchman, all sitting across from a pair of bounty hunters, though they prefer the term “harvesters of souls.” As the story progresses, each passenger shares their story. The trapper is an uncouth, uncivilized frontiersman who talks too much and thinks that all people are no different than ferrets. There is no “divine spark” to be found, no greater human mysteries to be unlocked. Just base, animal instincts. No, the religious woman scoffs, all people are most certainly not the same. The world is split into the upright and sinners, and from her pharisaical viewpoint, the righteous are rewarded for their stringent rule-following.

The Frenchman sitting next to her scoffs, poking holes in her moral code, and claiming the world consists of the lucky and the unlucky. No one can really fully understand another human being, and life is a mystery. Any attempt to understand it is foolish. The Frenchman is the closest avatar for how the Coen brothers are often seen, as amused cynics, pointing out the absurdity of the human need to find meaning in a senseless universe. But while there might be elements of the Trapper, the Woman, and the Frenchman in the Coen brothers (and all of us), it's more likely they see themselves as the bounty hunters.

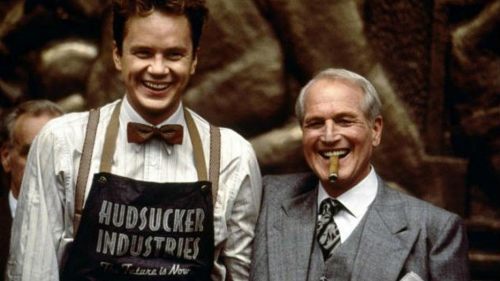

The two bounty hunters, played perfectly by Jonjo O’Neill (the Englishman) and Brendan Gleeson (the Irishman), take over the back half of "The Mortal Remains." Much like Joel and Ethan Coen’s working relationship - the brothers write, direct, and edit their movies together - the two bounty hunters are a perfect team, each complementing the other. The Englishman describes their methods of killing their targets, as their increasingly alarmed audience stares, wide-eyed. The Englishman distracts his bounty targets with a story like “The Midnight Caller,” because people like a story, he says. They connect to the characters, because the people in the stories are “us, but not us, in the end especially. The midnight caller gets [the person in the story], but not me, I’ll live forever.” And then Clarence “thumps” them.

In an interview with The Observer shortly after their movie Hail, Caesar! was released, the Coen’s described their moviemaking strategy almost exactly as the bounty hunters ply their trade. “There’s a little bit of pulling the rug out from underneath you,” Joel said. “We get you invested, then shake the floor.” In this, the Coen’s sound an awful lot like the Frenchman - a cynic, who enjoys exposing the stupidity of others. But in an eerily intimate moment toward the end of "The Mortal Remains," the Englishman looks directly at the camera, and says “I do like looking into [the dying person’s] eyes as they try to make sense of it. I do. I do.”

“Make sense of what?” The Woman asks?

“All of it” The Englishman replies.

“And do they?” The Trapper asks.

After a long pause, the Englishman laughs and says “how would I know? I’m only watching!”

And this is why the Coen brothers make movies, not out of a smug sense of self-importance, although you can easily imagine there’s more than a little of the Frenchman in them. And it’s not because they want to confront us, their fellow passengers in the carriage car of life, with our own imminent demise just for giggles. It’s because the Coen brothers are trying to make sense of this absurd world, where goodness and evil, and sense and senselessness, seem to exist side by side. Life may be absurd, but they can’t stop looking for some sort of transcendent meaning in it anyway. And so they make movies both to explore the mystery inside themselves, but also in us. And as we watch their films, they watch us, waiting to see if we can find some sort of meaning too.

Maybe this is why Marge Gunderson - the pregnant, good-hearted cop from Fargo - remains the Coen Brothers most beloved character. She represents the best of us, and the best of them, sincerely dedicated to doing good, baffled at how such unspeakable evil and randomness can exist, refusing to be tainted by it.

The Coen Brothers, in other words, are just like us, on this carriage together heading to the same place, looking for answers as to what comes next.