IN FABRIC Review: Dressed To Kill

Peter Strickland, most noted for his excellent The Duke of Burgundy, is probably one of the more idiosyncratic auteurs working in film today, and In Fabric finds him jumping into an entirely new style and form. Part giallo, part horror-comedy, part anti-consumerist diatribe, In Fabric at once feels alien in its conception and entirely hypnotic in its execution. Am I entirely convinced that all the relentless absurdity and startling turns make for a great and cohesive cinematic whole? Not really. But am I fascinated enough to suggest you judge for yourself? Absolutely.

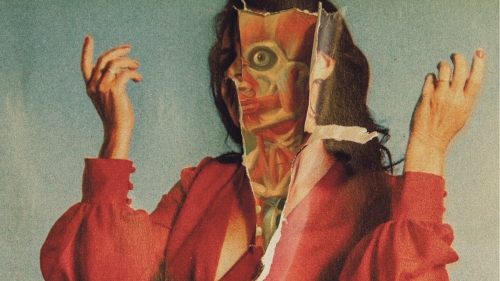

In Fabric is about a dress. It’s a sexy red dress, size 36, that somehow seems to magically fit anyone who wears it. And this dress has murderous intent. We initially see it come into the possession of Sheila (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), a recent divorcee whose son’s girlfriend gets on her nerves and whose bosses at the bank keep giving her inappropriate coaching on formality and social etiquette. She tries dating, though the results from the service she uses are less than ideal. So she buys the dress from a department store, only for her life to get all the stranger for the dress’s presence. Her washing machine goes on the fritz with the dress inside, cutting Sheila’s arm as she tries to stop it. A random dog attacks her and appears to rip the dress apart, only for the dress to return undamaged. Her son’s girlfriend sees the dress stalking her from the ceiling. The dress ominously grinds its hanger in the wardrobe at night. And yes, the dress kills.

These vignettes are seemingly random and informed by a strange sense of comedic timing, particularly when the oddly lyrical and robotic shop attendant, Miss Luckmore (Fatma Mohamed), is on screen, either attending Sheila in the shop with a string of unnecessarily verbose epithets or performing bizarre rituals with mannequins that bleed vaginally and sprout pubic hair. There isn’t so much a coherent theme that ties the film together as a series of motifs, emphasizing issues of body image, advertising, the illusion of civility, professional decorum as predation and discrimination, and capitalist coercion. The result is almost farcically broad in its social critiques and oblique symbolism, but given how the film seems to have a sense of humor about its own pretentions, that may be part of the underlying joke. But it also might just be a pretentious movie being pretentious.

In Fabric will probably lose a lot of people at about the halfway point, where the film takes a rather sudden shift, not in tone, but in subject, which eventually ties back around to Sheila’s story but is also jarringly detached from it. In terms of the surrealist tone the film had thus far established, the twist isn’t exactly out of place, but it still rather firmly cements the film into two distinct halves that don’t really mesh with each other organically or even narratively. It almost seems as if the film would have been better served to an anthology format, though the length of the disparate narratives seems to preclude that. As with everything in this movie, there’s little that is generally recognizable as good or bad cinematic storytelling, but calling such a shift intellectually challenging would still probably be a bit of a stretch. It really ends up just being one more surreal turn to cope with, in a film that is foundationally built on being confrontationally absurd.

If In Fabric were a smidge more self-serious, I probably couldn’t recommend it, since it really is a mishmash of ideas wrapped in the weave of a completely silly killer dress conceit. But Peter Strickland does seem to have a sense of irony about his pretentious swipe at his personal capitalist bugbears, so while the experience is in some ways impenetrable, you can at least laugh at some of the sillier lines of dialogue and shock-value imagery along the way.